Texten är skriven av Tim Foxley för FARR. Tim Foxley har mångårig erfarenhet av analytiskt och strategiskt arbete med särskilt fokus på Afghanistan.

Afghanistan in 2021 and the situation facing returning asylum seekers.

Afghanistan has been in a complex and protracted conflict for over four decades. Although some economic and developmental progress has certainly been made since the ejection of the Taliban in 2001 – infrastructure, education, human rights – many problems remain, including poor governance and corruption. Afghanistan is rated as the least peaceful country on the planet.[1] The risk of a collapse back into civil war is real.[2]

Thousands of young Afghans have been in Europe for years, pressing claims for asylum. If unsuccessful, there are many challenges facing them in Afghanistan. In June 2020, the Swedish Migration Agency revised and updated its position on the assessment of Afghan asylum applications. Six months on, little has changed for the better in Afghanistan. The American government agency, SIGAR, assessed that, in the last quarter, US airstrikes had increased, the number of insurgent IED attacks had increased by 17% and by the end of 2020 unemployment in the country was projected to have risen from 24% in 2019 to 38%.[3] This short article is intended to revise and highlight the range of conflict-related issues, including social and economic problems, that will present challenges to young Afghans who may have to return to their country of origin in 2021 and beyond.

Violent Attacks

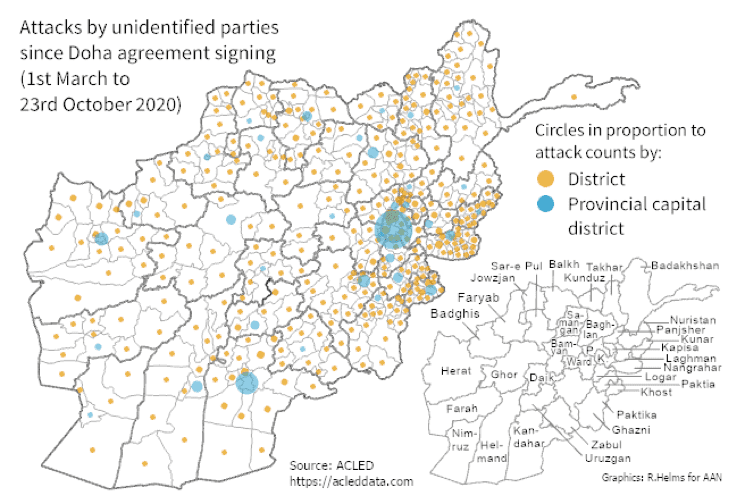

The security situation is fragile and fluid. The Taliban continue to fight across the large majority of the country.[4] It is unclear how they see their future role in society, but they do not look well-disposed to compromise. Other “spoilers”, such as Islamic State, will attempt to destabilise, perhaps targeting minorities, in order to trigger wider sectarian conflict.[5]

There is growing pessimism for the future. The International Crisis Group noted in January 2021:

…the Afghan government’s top figures now openly warn that full withdrawal [of US forces] could bring about state fracture and […] a peace deal giving the Taliban too much power will result in wider civil war.[6]

Every province is suffering from conflict-related violence.[7] Most returned asylum seekers are sent straight to Kabul.

The Taliban control many areas of the country, making extensive use of checkpoints along key roads, including up to the outskirts of major cities.

…The hard-line Islamist group has set up makeshift check posts along Afghanistan’s main highway connecting the capital, Kabul, in the east to Kandahar, the second city in the south. The province contains the middle stretch of Highway 1, which is more than 500 kilometers long…scores of travelers report intimidation or harassment as the Taliban snatches smartphones and, in some instances, copies phone data to prove what the hard-line Islamist movement considers suspicious activity… in recent years the Taliban has established control over stretches of major highways across Afghanistan where they comb through thousands of smartphones every week.[8]

Taliban checkpoint in Ghazni

In Kabul the Taliban have dramatically increased the number of attacks, aiming at Afghan citizens and government officials, including journalists, civil and human rights activists, judges and doctors, as well as military and police personnel.[9] There is a growing sense that the situation is worsening. On the 24th of August 2020, the New York Times reported:

Mornings in the city begin with ‘sticky bombs,’ explosives slapped onto vehicles that go up in flames…The city has taken on an air of slow-creeping siege. At least 17 small explosions and assassinations have been carried out in Kabul in the past week…[10]

During their time in Europe, many Afghans have adopted Western fashion, cultural and linguistic trappings. In rural parts of the country, where conservative Islamic values and the Taliban often dominate, this can be perceived negatively.[11] This does not automatically guarantee that returnees will be targeted, but there is risk:

…reports of individuals who returned from Western countries having been threatened, tortured or killed…on the grounds that they were perceived to have adopted values associated with these countries, or they had become “foreigners” or that they were spies for or supported a Western country. Returnees are reportedly often treated with suspicion…leading to discrimination and isolation.[12]

Food and housing insecurity

Displaced Afghans mention lack of housing, access to food and unemployment as the top three key challenges.[13] Resources are limited for returnees.[14] On arrival at the airport, some returnees report being respectfully treated and others with indifference.[15] Reports of verbal and physical abuse directed towards the returnees have also been credibly reported.[16]

Estimates suggest a third of the population face high levels of acute food insecurity.[17] The UN identified 380,000 people newly displaced in 2020 (of which 60% were under 18).[18]

Displacement due to ongoing conflict and natural disasters is continuing to drive humanitarian needs in Afghanistan…The 2020 Humanitarian Needs Overview estimates that close to a million people on the move will need humanitarian assistance by the end of the year.[19]

Finding safe and secure accommodation is a significant challenge. The majority of urban housing are slums.[20]

…The lack of adequate land and affordable housing in the urban area forces most new and protracted IDPs in Kabul to reside in tents, mud brick and tarpaulin shelters in one of the more than 55 informal and illegal settlements around the city…limited job opportunities, few or no social protection nets, poor shelter/housing conditions, impeded access to education and healthcare and the continuous fear of eviction…[21]

High unemployment and limited access to healthcare

The employment situation in Afghanistan is very poor, exacerbated by the corona pandemic.[22] A report by Gallup concluded in September 2019 that the job market was the bleakest on record. A report from February 2020 summarised the core problems:[23]

…the two biggest challenges facing the Afghan workforce is underemployment and lack of job opportunities, resulting in 80-90 percent of the Afghan labor force being forced into the informal economy surviving off subsistence farming and petty trade… The informal economy plagued with numerous problems placing workers’ health, safety and livelihoods at risks, such as hazardous working environments, very low paying jobs, harassment by city management authorities, and a lack of job security.[24]

Unemployment is also a security problem: it can drive men to work for insurgent groups out of desperation.[25]

Returnees are at risk of exploitation and trafficking.[26] Some Afghans are recruited and sent to Iran to fight in Syria.[27] Brick factories exploit young workers in appalling conditions.[28]

NGOs report an increase in human trafficking within Afghanistan. Traffickers exploit men, women and children in bonded labor – a form of forced labour…Afghan returnees from Pakistan and Iran and internally displaced Afghans are vulnerable to labor and sex trafficking…[29]

There are also reported risks of encountering insurgent recruiters amongst informal settlements and other less secure areas in the capital:

…sources report on the risk of recruitment of IDPs or inhabitants of informal settlements in Kabul by insurgent groups and the possible radicalisation of returnees and people deported from Europe…[30]

Afghanistan has been struggling to respond to the Corona pandemic. The Health Ministry suggests that a third of the population may have been infected.[33] The population do not have access to basic hygiene procedures. Funding, equipment and staff are limited.[34]

Summary

The security, political and economic situation remains bleak in Afghanistan and is likely to remain so for the next 5 – 10 years. There are major challenges for young Afghans returning to Afghanistan. The conflict is extensive – no province is entirely safe. There are other risks in Kabul and the country as a whole, stemming from the broader security, social and economic problems. There are risks of exploitation and destitution. Importantly, the UNHCR believes Kabul is not viable for returnees.

Tim Foxley 3 February 2021

[1] ‘Global Peace Index, 2020’, Institute for Economics and Peace, June 2020, http://visionofhumanity.org/reports/

[2] Mehrdad, E., ‘Afghans Celebrate Reduction in Hostilities But Fear Civil War’, The Diplomat, 26 Feb. 2020.

[3] ‘50th Report to Congress, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, 30 Jan. 2021, https://www.sigar.mil/quarterlyreports/index.aspx?SSR=6

[4] Constable, P., ‘Taliban shows it can launch attacks anywhere across Afghanistan, even as peace talks continue’, The Washington Post, 25 Oct. 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/afghanistan-violence-peace-talks-taliban/2020/10/25/4161716e-156c-11eb-a258-614acf2b906d_story.html

[5] Foxley, T., ‘ISKP attacking minorities in Afghanistan’, Afghanhindsight report, 25 Mar. 2020, https://afghanhindsight.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/iskp-attacking-minorities-in-afghanistan/ , https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/24/two-bomb-blasts-kill-at-least-14-in-afghanistan-officials

[6] ‘What Future for Afghan Peace Talks under a Biden Administration?’, ICG Crisis Briefing, N0. 165, 13 Jan. 2021, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/afghanistan/b165-what-future-afghan-peace-talks-under-biden-administration

[7] Kate, C., and Helms, R., ‘Behind the Statistics: Drop in civilian casualties masks increased Taliban violence’, AAN Report, 27 Oct. 2020, https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/war-and-peace/behind-the-statistics-drop-in-civilian-casualties-masks-increased-taleban-violence/

[8] Taseer, H., ‘Taliban Mines Afghan Phone Data In Bid For Control’, RFE/RL, 30 Oct. 2020, https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/taliban-mines-afghan-phone-data-in-bid-for-control/30919738.html

[9] Harding, L., ‘Two female judges shot dead in Kabul as wave of killings continues’, The Guardian, 17 Jan. 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/17/two-female-judges-shot-dead-in-kabul-as-wave-of-killings-continues

[10] Mushal, M., Faizi, F., and Rahim, N., ‘With Delay in Afghan Peace Talks, a Creeping Sense of “Siege” Around Kabul’, The New York Times, 24 Aug. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/23/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-attacks-kabul.html

[11] Sridharan, V., ‘Afghan Taliban execute a lecturer and a student but no one seems to know why’, International Business Times, 1 Jan. 2018, https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/afghan-taliban-execute-lecturer-student-no-one-seems-know-why-1653300

[12] ‘UNHCR ELIGIBILITY GUIDELINES FOR ASSESSING THE INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION NEEDS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS FROM AFGHANISTAN’, UNHCR report HCR/EG/AFG/18/02, 30 Aug. 2018, pp.46-47.

[13] ‘Going “home” to displacement: Afghanistan’s returnee-IDPs’, IDMC Report, Dec. 2017.

[14] ‘Afghan returnees face economic difficulties, unemployment’, The World Bank, 14 July 2019, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/07/14/afghan-returnees-face-economic-difficulties-unemployment

[15] ‘From Europe To Afghanistan: Experiences of Child Refugees’, Save The Children report, 2018, p34.

[16] Dearden, L., ‘Afghan police start beating asylum seekers in front of Danish officers on deportation flight’, The Independent, 16 May 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/afghanistan-police-beat-asylum-seekers-danish-officers-deportation-flight-kabul-refugee-returns-safe-a7739176.html

[17] ‘Afghanistan: Over 11 million people acutely food insecure due to COVID-19, high food prices, reduced income and conflict’, IPC, accessed 25 Jan 2021, http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipcinfo-website/alerts-archive/issue-28/en/

[18] ’Afghanistan: Snapshot of Population Movements (January to December 2020), UN OCHA report, 23 Jan. 2021.

[19] ‘Asia and the Pacific Weekly Regional Humanitarian Snapshot’, OCHA Report, 17 Mar. 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/philippines/asia-and-pacific-weekly-regional-humanitarian-snapshot-10-16-march-2020

[20] ‘State of Afghan Cities’, Afghan Ministry of Urban Development Affairs report, 2015.

[21] ‘Afghanistan: Security Situation in Kabul City’, Cedoca, 8 Apr. 2020, pp.32-35.

[22] ‘Afghanistan Faces “Grim” Economic Outlook as Pandemic Wipes Out Growth: World Bank’, Reuters, 15 July 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2020/07/15/world/asia/15reuters-health-coronavirus-afghanistan-economy.html

[23] Archer, K., ‘Inside Afghanistan: Job Market Outlook Bleakest on Record’, Gallup, 9 Sep. 2019, https://news.gallup.com/poll/266555/inside-afghanistan-job-market-outlook-bleakest-record.aspx

[24] Ahmadzai, S., ‘Creating New Jobs in Afghanistan: What Do We Know and What Should We Do?’, Afghanistan Times, 25 Feb. 2020, http://www.afghanistantimes.af/creating-new-jobs-in-afghanistan-what-do-we-know-and-what-should-we-do/

[25] Safi, M., ‘Youth Unemployment in Afghanistan’, Pax Populi, 10 Nov. 2014, http://www.paxpopuli.org/youth-unemployment-in-afghanistan/#sthash.9Q9Nm4J3.dpbs

[26] Ferrie, J., ‘Human trafficking on the rise in Afghanistan despite new laws’, Reuters, 29 Mar. 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-humantrafficking-laws/human-trafficking-on-the-rise-in-afghanistan-despite-new-laws-idUSKBN1H52U8

[27] ‘Iran recruits Afghan teenagers to fight war in Syria’, Deutsche Welle, 5 May 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/iran-recruits-afghan-teenagers-to-fight-war-in-syria/a-43634279

[28] ‘Children in kilns found in deplorable situation’, Pajhwok News, 26 Nov. 2014, https://www.pajhwok.com/en/2015/03/10/children-kilns-found-deplorable-situation

[29] ‘Country Narratives, Afghanistan’, US State Department, 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report, 2019, pp.58-61.

[30] ‘Afghanistan: Security Situation in Kabul City’, Cedoca, 8 Apr. 2020, p.35.

[31] Azad, S., ‘Endless Conflict in Afghanistan Is Driving a Mental Health Crisis’, Foreign Policy, 27 Sep. 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/27/endless-conflict-in-afghanistan-is-driving-a-mental-health-crisis/

[32] Pignataro, J., ‘War, Bombings And Poverty In Afghanistan: 10 Million Afghans Have Mental Illness Or Distress After Decades Of Conflict’, I B Times, 20 Oct. 2016, http://www.ibtimes.com/war-bombings-poverty-afghanistan-10-million-afghans-have-mental-illness-or-distress-2434837

[33] Gul, A., ’10 Million Afghans Likely Infected and Recovered From COVID-19: Survey’, VoA, 5 Aug. 2020, https://www.voanews.com/south-central-asia/10-million-afghans-likely-infected-and-recovered-covid-19-survey

[34] Quilty, A., ‘With Fake Hand Sanitizer and 12 Ventilators, Afghanistan Expects Millions of Coronavirus cases’, The Intercept, 2 Apr. 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/04/02/coronavirus-afghanistan/